Infield Fly Rule

The infield rule played a big role in the 2012 National League wild card game. In the eighth inning of the winner-take-all game between the Atlanta Braves and the St. Louis Cardinals Atlanta shortstop Andrelton Simmons came to bat with runners on first and second and hit a high, shallow pop up between Cardinals’ shortstop Pete Kozma and left fielder Matt Holliday. Kozma attempted to field it as he backpedaled but dropped the ball. It look as if the Braves would have the bases loaded with one out.

But wait. Left field umpire Som Holbrooke had called the infield fly rule, meaning Simmons was automatically out.

Outraged Braves fans began throwing debris on the field to protest the call, causing an eighteen minute delay. The Cardinals would end up winning the game 6-3 and advancing to the next round.

There is no doubt Holbrooke erred by waiting too long to call the ball an infield fly — it had just about hit the ground when he raised his hand up. Furthermore, there is a good argument to be made that Kozma needed more than ordinary effort to field the ball, and an infield fly shouldn’t have been called at all.

But while the execution of the infield fly role during the 2012 Wild Card was clearly flawed, the logic behind the somewhat mysterious regulation is very solid. Here the infield rule, as defined by the official rules on MLB.com.

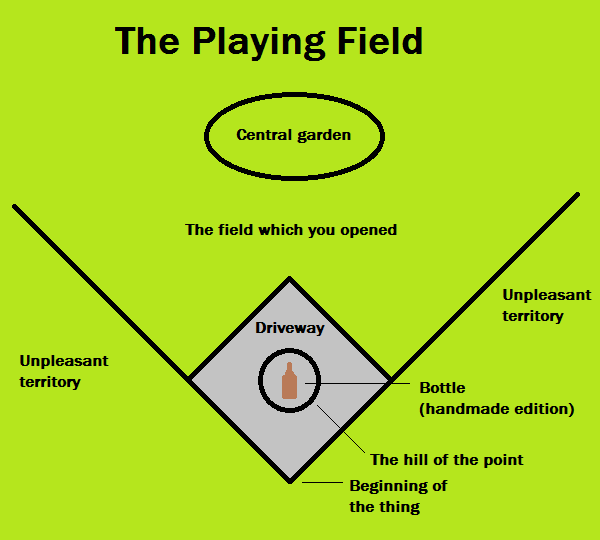

“An infield fly is a fair fly ball (not including a line drive nor an attempted bunt) which can be caught by an infielder with ordinary effort, when first and second, or first, second and third bases are occupied, before two are out. The pitcher, catcher and any outfielder who stations himself in the infield on the play shall be considered infielders for the purpose of this rule.

When it seems apparent that a batted ball will be an Infield Fly, the umpire shall immediately declare Infield Fly for the benefit of the runners.”

The infield fly rule is essential because if it didn’t exist infielders would deliberately drop pop ups when there are less than two outs and runners on first and second or when there are less than two outs and the bases are loaded. They would do this because the baserunners would be forced to stay close to the base until the infielder (deliberately) dropped the ball and then the infielder would be able to pick the ball up and start a double play.

Occasionally you will see a legal variation of this strategy when there is a fast runner on first and slow runner hits a pop up. The infielder will sometimes let the pop up fall and then throw the ball to second, forcing out the faster runner and replacing him at first with a slow footed player.

This play is rare because most teams don’t want to risk the infielder kicking or losing control of the dropped fly ball (thus recording no outs) just to replace a fast runner with a slower one. However the calculus would be different if instead of just one out the fielder could completely kill a rally with a double play.

That is why baseball needs an infield fly rule. Just don’t trying tell that to Atlanta Braves fans.